During my first hospital pharmacy experience, I remember being awe-struck by the confidence exuding from the pharmacist when she gave her recommendations to the attending physicians and other members of the interprofessional team. She seemed at ease discussing the evidence supporting the recommendations. And when there was uncertainty about the next steps, she asked explicit questions to develop a more accurate assessment. I wanted to have this level of confidence in my clinical decision-making, but I was unsure about how to achieve it. I think every student (and resident) seeks to gain a high level of confidence but how can educators assess and cultivate it?

Before measuring confidence, we need to define it. Therein lies the initial problem. Confidence is tricky to define because it is not concrete – you can’t actually see it. It is a belief the action taken is right, proper, and effective.1 Clinical confidence is the certainty that a decision or action undertaken in the clinical setting is correct and will lead to the best outcome.

One of the interesting aspects of confidence is that it doesn’t always match with knowledge. This mismatch is known as the Dunning–Kruger effect whereby, based on our perceived knowledge, we overestimate our ability. In other words, some knowledge of the subject matter leads us to conclude we are more competent than we actually are when measured using objective tests.2

In a 2006 study, Valdez and colleagues compared second-year pharmacy students’ self-confidence scores regarding the treatment of dyslipidemia and hypertension to their scores on a multiple-choice exam. Confidence was measured using a 12-item questionnaire and rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=low confidence and 5=high confidence). Each confidence question was linked to a critical concept on the 21-item multiple-choice test. For example, students were asked to rank their confidence “identifying causes of resistant HTN” and this concept was evaluated on one or more items on the multiple-choice test. The confidence assessment (administered first) and multiple-choice test (administered second) were given immediately after students had received didactic instruction about the treatment of patients with dyslipidemia and hypertension. For most items on the test, there was little or no correlation between the students’ level of confidence (mean scores typically = 3.5 to 4.2) and whether (or not) they correctly answered the question. In other words, students who incorrectly answered questions about a concept were just a likely to rate their confidence as a 4 or 5 (moderate-high or high) as students who correctly answered the question. The same confidence and knowledge assessments were administered 4 months later. Interestingly, student confidence remained relatively high (despite the passage of time); however, their retention of the knowledge decreased significantly, by about one letter grade.3 Since the multiple-choice exam was administered after the confidence assessment, it seems clear that students were not able to accurately judge their knowledge. Moreover, as we all know, in the absence of use, knowledge diminishes over time as the “use it or lose it” phrase implies. And yet, students continued to be quite confident in their knowledge even after doing poorly on an exam and with the passage of time.

While learners may over-estimate their knowledge and skill, is it possible to increase their confidence using novel teaching techniques? In a pharmacotherapy laboratory course, teachers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy compared the use of paper-based patient-case narratives to the same cases deployed in a simulated Case Scenario/Critical Reader (CSCR) Builder program. The hypothesis was that the simulated environment would increase student engagement, knowledge, and confidence. Each group – paper-based and simulation— completed a 13-item pre-experience confidence survey (0-39 score) regarding their self-perceived ability to manage a patient with osteoarthritis. The simulated-case students had access to an electronic medical record (EMR), could navigate through a series of multiple-choice questions, and could gather information from the simulated patient and physician. The simulation group reported significantly increased confidence in their ability to assess the medication regimen and document the encounter (p < 0.05) when compared to the paper-based group. However, the mean SOAP scores were not significantly different. So, the instructor’s effort (> 20 hours) put into creating a simulated patient case may have increase student confidence but its impact on skill appears to be marginal.4

Similarly, instructors at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Pharmacy designed a rigorous third-year pharmacy elective where students gained experience with exercise counseling. The students created pamphlets and monitored a patient over a 4-week period. Students who took the elective were more confident counseling patients about exercise and remained more confident 6 months later when compared to students who did not enroll in the course.5 Thus, engaging students in practical, hands-on experiences appear to be an important aspect of developing confidence.6

Developing one’s confidence is an important step in becoming an effective clinician. Students may be misled by high exam scores into believing their clinical abilities are well developed. This can be problematic because overestimation may result in students inadvertently practicing beyond their level of competence, resulting in patient harm. However, providing students with opportunities to simultaneously employ their knowledge through concrete, real-life experiences improve their clinical confidence and competence.6

Recommendations to help students more accurately assess their confidence and competence:

- Measure confidence before administering knowledge and/or skill assessments

- Provide students with engaging ways to learn and test their skills

- If students overestimate their knowledge or skill, challenge them to identify where their knowledge or skill is lacking

- Personal experience, providing students autonomous practice, can help students grow their confidence and competence

Questions yet to be answered:

- What factors influence students’ perception of confidence?

- What is the relationship between clinical experience and confidence?

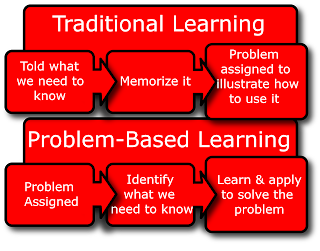

- What effect does problem-based learning (and other forms of classroom-based problem-solving) have on clinical confidence?

References

- Confidence. Merriam-Webster's dictionary. 2019.

- Kruger J1, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999; 77: 1121-34.

- Valdez CA, Thompson D, Ulrich H, Bi H, Paulsen S. A Comparison of Pharmacy Students’ Confidence and Test Performance. Am J Pharm Ed. 2006; 70 (4) Article 76.

- Barnett SG, Gallimore CE, Pitterle M, Morrill J. Impact of a Paper vs Virtual Simulated Patient Case on Student-Perceived Confidence and Engagement. Am J Pharm Ed 2016; 80: Article 16.

- Persky AM. An Exercise Prescription Course to Improve Pharmacy Students’ Confidence in Patient Counseling. Am J Pharm Ed 2009; 73: Article 118.

- Jih JS, Shrewsbury RP. Student Self-Analysis of Their Nonsterile Preparations and its Effect on Compounding Confidence. Am J Pharm Ed 2018; 82: Article 6473.