Howard Barrows, one of the earliest champions of problem-based learning (PBL), once defined it as “the learning that results from the process of working toward the understanding or resolution of a problem.”1 Since its first use at McMaster University School of Medicine in the 1960s, PBL has been used by many other health disciplines including nursing and pharmacy.2,3 PBL really took off in pharmacy education in the early 2000’s when the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards proclaimed that the Doctor of Pharmacy curriculum should promote “lifelong learning through the emphasis on active, self-directed learning and … teaching strategies to ensure the adeptness of critical thinking and problem-solving.”4 This theme continues today in the 2016 ACPE accreditation standards.5

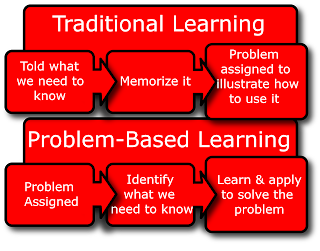

As an instructional method, PBL is primarily designed to empower learners to solve a problem through the application of knowledge. Given its wide range of implementations, there is no universally agreed definition of problem-based learning. Traditionally, PBL usually involves a small group of students with an elected (or appointed) leader and scribe. A faculty member serves as the facilitator whose primary role is to observe the group dynamics and ensure the intended learning objectives are achieved but does not provide any direct instruction. The groups review “trigger material,” such as a patient case or clinical scenario with no prior exposure and without instruction by the facilitator.6 Some institutions like the University of Southern California implemented “assisted” PBL, whereby didactic lectures are used to enhance the students’ background knowledge, but the technique still contains elements common to a traditional PBL experience.7 However, despite some differences in their implementation in pharmacy education, there are several common themes: discussions in small groups; hypothetical or real case scenarios; facilitation focused on group progress; and self-direction combined with collaborative learning. PBL uses problems in order to develop problem-solving skills as well as reinforce existing and acquire new knowledge.8,9 Thus, PBL was an obvious choice for many schools and colleges of pharmacy to meet their need for a self-directed form of active learning. However, despite the level of “deep learning” provided by PBL, a common concern is that it may not lead to the same level of performance on standardized exams, which often focus on knowledge recall and memorization.6

Various disciplines and institutions have been experimenting with how best to implement PBL and to what degree this teaching strategy should be used throughout the curriculum. Should it be implemented in a single year as preparation for advanced practice experiences? Or used exclusively throughout the entire curriculum? Or sporadically as a substitute for case-based learning? Several investigators have now published about their experiences with PBL. In pharmacy education, feedback from students and educational performance data provide some insight into the methodology’s successes.

In a comparative study conducted at the University of Southern California, student rotation performance was compared after students participated in either PBL (Class of 1995) or received traditional didactic lectures (Class of 1994) during their third year of the pharmacy curriculum.10 Both groups received the same instruction in the first year of the curriculum and had similar mean GPAs (2.88 vs. 2.9, p=0.1). However, when comparing the graduating classes of 1994 and 1995’s mean GPA during experiential rotations, the PBL group was had significantly higher GPAs for both elective and required rotations (3.29 and 3.38 vs. 3.09 and 3.11, respectively). The authors concluded that PBL produced positive outcomes during fourth-year advanced practice experiences because it increased students’ ability to engage in self-directed learning, increased their independence, and enhanced their decision-making skills. The authors felt these results were important given that the functions, responsibility, and skillsets required during the fourth year of the curriculum are similar to that of pharmacists providing pharmaceutical care.

A relatively recent meta-analysis analyzed 5 studies conducted in Canada, the US, and UK comparing the outcomes of PBL to conventional didactic instruction in pharmacy courses.11 The primary endpoints were midterm and final grades, as well as subjective evaluations. While both the midterm (OR = 1.46; 1.16–1.89) and final (OR = 1.60; 1.06–2.43) grades were significantly higher in the PBL groups, subjective evaluations between the two did not differ. The authors concluded that PBL yielded superior student performance on assessments, while also promoting clinical reasoning and self-directed learning. However, the authors did note that the relatively small sample size may not be large enough to ensure the generalizability to other pharmacy programs.

Student assessment of PBL seems largely positive as well. In one survey, graduates from the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy were surveyed regarding PBL and the adequacy of their preparation for Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (APPEs).12 In disease state/drug therapy discussions, efficient retrieval of current medical literature, and patient-specific evaluation of drug regimens, 50% or more of graduates believed PBL had provided them with above average preparation in these areas. The authors point out that the success of PBL shouldn’t be solely measured by student success on licensing exams, but also students’ perceptions and self-confidence to enter practice.

Though the impetus for many colleges and schools of pharmacy to move toward PBL may have been, in part, to satisfy accreditation standards, it would seem that the results, at least in pharmacy education, suggest this instructional technique is effective. There are multiple sources of data that suggest the PBL is as good as, or possibly superior to, more passive learning strategies such as didactic instruction. However, while assessments and correlations with academic performance are helpful in gauging its efficacy and benefits, it can difficult to truly assess the student experience.

Various disciplines and institutions have been experimenting with how best to implement PBL and to what degree this teaching strategy should be used throughout the curriculum. Should it be implemented in a single year as preparation for advanced practice experiences? Or used exclusively throughout the entire curriculum? Or sporadically as a substitute for case-based learning? Several investigators have now published about their experiences with PBL. In pharmacy education, feedback from students and educational performance data provide some insight into the methodology’s successes.

In a comparative study conducted at the University of Southern California, student rotation performance was compared after students participated in either PBL (Class of 1995) or received traditional didactic lectures (Class of 1994) during their third year of the pharmacy curriculum.10 Both groups received the same instruction in the first year of the curriculum and had similar mean GPAs (2.88 vs. 2.9, p=0.1). However, when comparing the graduating classes of 1994 and 1995’s mean GPA during experiential rotations, the PBL group was had significantly higher GPAs for both elective and required rotations (3.29 and 3.38 vs. 3.09 and 3.11, respectively). The authors concluded that PBL produced positive outcomes during fourth-year advanced practice experiences because it increased students’ ability to engage in self-directed learning, increased their independence, and enhanced their decision-making skills. The authors felt these results were important given that the functions, responsibility, and skillsets required during the fourth year of the curriculum are similar to that of pharmacists providing pharmaceutical care.

A relatively recent meta-analysis analyzed 5 studies conducted in Canada, the US, and UK comparing the outcomes of PBL to conventional didactic instruction in pharmacy courses.11 The primary endpoints were midterm and final grades, as well as subjective evaluations. While both the midterm (OR = 1.46; 1.16–1.89) and final (OR = 1.60; 1.06–2.43) grades were significantly higher in the PBL groups, subjective evaluations between the two did not differ. The authors concluded that PBL yielded superior student performance on assessments, while also promoting clinical reasoning and self-directed learning. However, the authors did note that the relatively small sample size may not be large enough to ensure the generalizability to other pharmacy programs.

Student assessment of PBL seems largely positive as well. In one survey, graduates from the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy were surveyed regarding PBL and the adequacy of their preparation for Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (APPEs).12 In disease state/drug therapy discussions, efficient retrieval of current medical literature, and patient-specific evaluation of drug regimens, 50% or more of graduates believed PBL had provided them with above average preparation in these areas. The authors point out that the success of PBL shouldn’t be solely measured by student success on licensing exams, but also students’ perceptions and self-confidence to enter practice.

Though the impetus for many colleges and schools of pharmacy to move toward PBL may have been, in part, to satisfy accreditation standards, it would seem that the results, at least in pharmacy education, suggest this instructional technique is effective. There are multiple sources of data that suggest the PBL is as good as, or possibly superior to, more passive learning strategies such as didactic instruction. However, while assessments and correlations with academic performance are helpful in gauging its efficacy and benefits, it can difficult to truly assess the student experience.

I recently had my first experiences as a PBL facilitator. When I begin a PBL session, I always ask the students what their expectations of the facilitator are. They frequently asked for clinical pearls. While I believe that PBL provides more robust, “real world” examples and deeper learning as a whole, I do think it is valuable for teachers to share “clinical pearls” with students. Traditional PBL offers little opportunity for teachers to share “pro tips,” instead emphasizing how to learn, apply, and approach a complex problem. Though assessments and surveys may indicate that students are more prepared for practice and are generally satisfied with PBL as a learning method, it does leave me wondering if learners are missing out on “fact-based learning” that more traditional methods of instruction afford.

References

- Barrows H. A taxonomy of problem-based learning methods. Med Educ. 1986;20(6):481-486.

- Creating Lifelong Learners. London: English National Board; 1994.

- Ross L, Crabtree B, Theilman G, Ross B, Cleary J, Byrd H. Implementation and Refinement of a Problem-based Learning Model: A Ten-Year Experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71: Article 17.

- American Council on Pharmaceutical Education. Chicago; 2000:52-53.

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. 2016. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy degree. Available at https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf.

- Wood D. Problem based learning. BMJ. 2003;326(7384):328–30.

- Romero R, Eriksen S, Haworth I. Quantitative Assessment of Assisted Problem-based Learning in a Pharmaceutics Course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(4):Article 66.

- Savery J. Overview of Problem-based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning. 2006;1(1):9-20.

- Barrows H. Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 1996;Winter 1996(68):3-12

- Nii L, Chin A. Notes Comparative Trial of Problem-Based Learning Versus Didactic Lectures on Clerkship Performance. Am J Pharm Educ. 1996;60: 162-164.

- Galvao T, Silva M, Neiva C, Ribeiro L, Pereira M. Problem-Based Learning in Pharmaceutical Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Scientific World Journal. 2014; Feb:1-7.

- Hogan S, Lundquist L. The Impact of Problem-based Learning on Students' Perceptions of Preparedness for Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70:Article 82.

No comments:

Post a Comment