by Cynthia Uche, Doctor of Pharmacy Candidate, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy

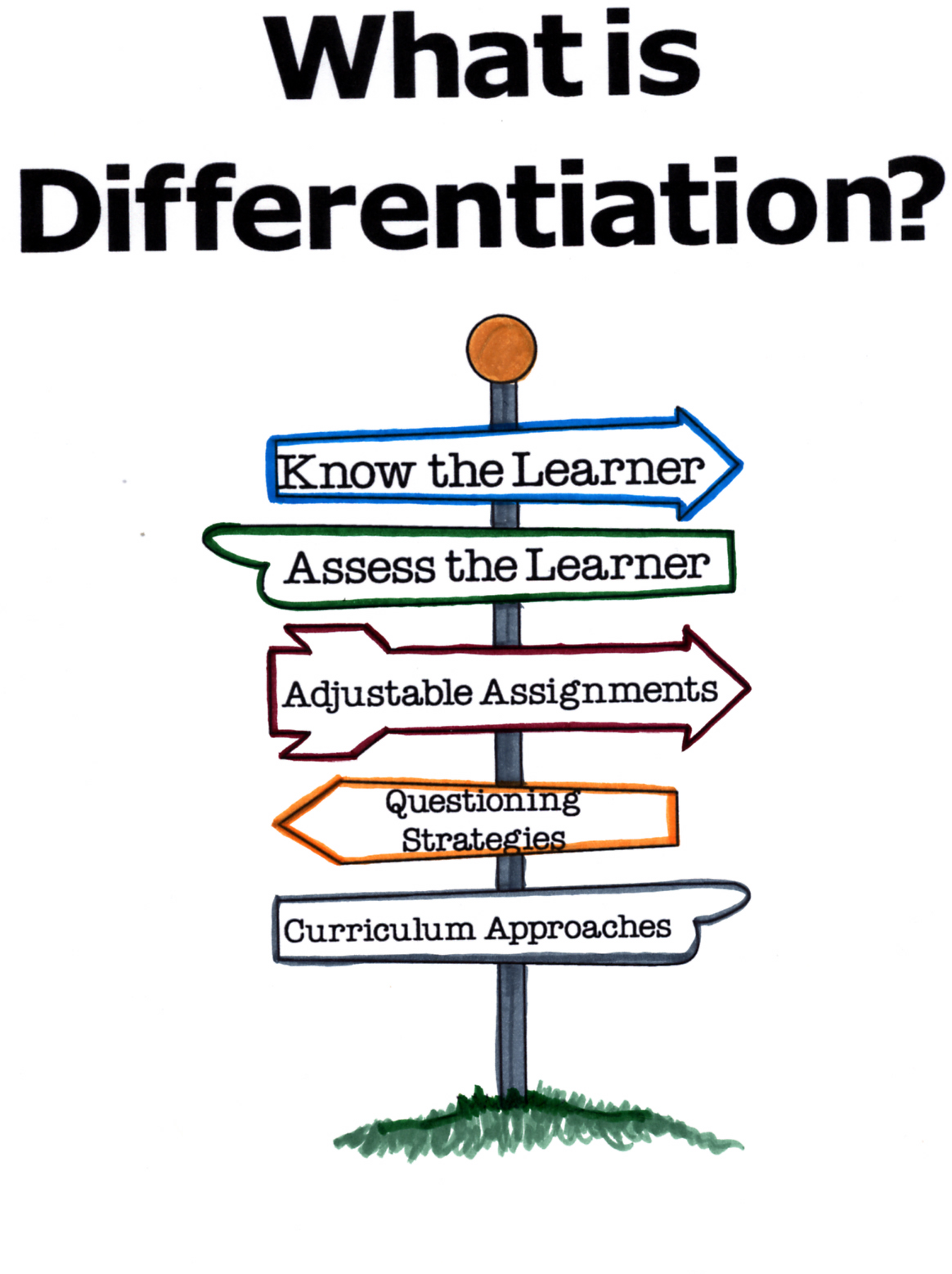

The recognition that all students do not learn in the same paves the way for differentiated instruction, or DI. DI is a type of instruction that is inclusive of different types of learners.1,2,3 DI addresses the varying learning styles of students within the classroom.1,2,3 Each student has different learning preferences and the aim of DI is to create options for the delivery of a lesson. This method of instruction is a form of multimodal learning and it is often applied in today’s classrooms. DI is part of the standard to which teachers and instructors are assessed.4,5 Students’ needs, motivations, and abilities are varied, therefore, part of the instructor’s task is to construct lessons that address each student’s needs. DI principles are based on the idea of multiple intelligences, completing tasks/activities that are socially relevant to the student, along with incorporation of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning methods into each lesson.1,3,5

The recognition that all students do not learn in the same paves the way for differentiated instruction, or DI. DI is a type of instruction that is inclusive of different types of learners.1,2,3 DI addresses the varying learning styles of students within the classroom.1,2,3 Each student has different learning preferences and the aim of DI is to create options for the delivery of a lesson. This method of instruction is a form of multimodal learning and it is often applied in today’s classrooms. DI is part of the standard to which teachers and instructors are assessed.4,5 Students’ needs, motivations, and abilities are varied, therefore, part of the instructor’s task is to construct lessons that address each student’s needs. DI principles are based on the idea of multiple intelligences, completing tasks/activities that are socially relevant to the student, along with incorporation of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning methods into each lesson.1,3,5

Establishing clear objectives is the first step. In order to deliver content well, the content must be relevant to the students. Choosing a variety of instructional methods is the key to applying the DI method. For example, use of visual aids and textbooks for visual learners and incorporation of note taking for the tactile learners.1,5 Another important component of DI is addressing the learning environment. The learning environment needs to be safe and encourage learning. Rewarding students’ for effort, despite less than perfect performance, is important in establishing a safe learning environment.

After the delivery of content, instructors may use DI to allow students the option of showing mastery of the content based on their learning style.1,2 Kinesthetic learners may build a model and describe its relevance to the topic. Visual learners may wish to create a PowerPoint presentation or a graphic organizer that explains the assigned topic. Auditory learners may wish to deliver an oral report. Finally, learners who prefer to write may compose a written report based on the assigned content.1,3 Assessing effectiveness throughout each lesson, is an important aspect of DI. The infusion of formative and summative assessments during and following delivery of the lesson are great ways to assess student learning and progress. Multiple-choice questions that assess the students’ level of comprehension of the topic can be administered during and at the end of the lesson. In many classrooms, the instructor can employ student response software such as “clickers”, raising hands to indicated answer choices, or through traditional paper and pencil questions. Research has shown that DI is effective for learners of different cognitive abilities.1 The availability of options motivates students to take responsibility for their learning.1,4 One study found that student grouping based on learning styles improved collaborative learning.6 The accessibility of different options of assignments may better serve the students, if they work collaboratively, in groups, based on their similar learning styles.

With the expansion of course delivery to online classrooms, the application of DI methods to online learners is also important. Students enrolled in online courses have the same varied needs, experiences, intelligences, and learning styles as those enrolled in courses held in traditional classrooms.

In the online classroom, utilizing multimedia can help an instructor to differentiate the content, process, and outcomes. Interactive activities that foster cooperative learning, with shared ideas and open discussions among students, especially through online chat forums, are great tools for learning.2 According to the DI model, direct instruction and inquiry-based learning should also be incorporated into lessons.1 There needs to be a balance between all of these methods, no one method should be utilized more than the others.4,5 For instance, in a course that is delivered in a 50 minute period, direct instruction may comprise only 10-15 minutes of that period. After which, the instructor can then segue into other forms of instruction, such as inquiry-based learning. DI model encourages student-centered learning over instructor-led learning.5 This method inspires student investment and accountability for learning.1

As with any method of instruction, there are pros and cons of DI. DI requires a great deal of planning.1 More time is spent adjusting delivery of a lesson after formative assessment indicates that the delivery is less than optimal. Professional development needs to be dedicated to assisting instructors learn how to apply DI methods to their classes. Ultimately, the success of DI that has been observed in the traditional classrooms can be translated to online classes.

References

References

- Weselby C. What Is Differentiated Instruction, Examples of Strategies [Internet]. Concordia University: Teaching Strategies; 2014 Oct 1 [cited 2016 Mar 5].

- Hampel R, Stickler U. The use of videoconferencing to support multimodal interaction in an online language classroom. ReCALL. 2012; 2:116-137.

- Clayton K, Blumberg F, Auid DP. The relationship between motivation, learning strategies and choice of environment whether traditional or including an online component. Br J Educ Tech. 2010;3: 349-64.

- Landrum T, McDuffie K. Learning styles in the age of differentiated instruction. Exceptionality. 2010;18:6-17.

- Tomlinson CA. The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners [Internet]. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 1999 [cited on 2016 Mar 5].

- Alfonseca E, Carro RM, et al. The impact of learning styles on student grouping for collaborative learning: A case study. User Modeling & User-Adapted Interaction 2006;16:377.